They gathered in different ways. Some had big, public parties. Others gathered in a conference room as a small group. One watched from a villa in Tuscany.

Watching at home, John Kristick was able to reflect. When Qatar was awarded the 2022 World Cup in December 2010, it was at the expense of the United States’ bid led by Kristick as managing director. Seven years later, the U.S. teamed with Mexico and Canada for the first three-country World Cup bid. Back as managing director for the new bid, Kristick got in touch with the cities involved the first time around.

“Quite frankly, I wasn’t sure what the reaction would be,” he said. “Every one of them said, ‘We’re ready.’ Fast forward to June 2018 when the bid was chosen (by FIFA) and it was just a proud moment.”

Fast forward again to July 16 and FIFA — having delayed a host city announcement multiple times — was ready to reveal all. Those involved waited, watching as the decision was broadcast and streamed worldwide.

[2022 World Cup: Who’s Playing, How to Watch and Why Qatar is Hosting]

“I had over a decade of my life wrapped up into one announcement,” said Janis Burke, chief executive officer for the Harris County-Houston Sports Authority.

Finally, the announcement came: Atlanta, the Bay Area, Boston, Dallas, Houston, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Miami, New York/New Jersey, Philadelphia and Seattle were chosen to host matches in the United States.

“One would look at it and say, ‘It can’t be that complicated to do four, five, six matches in a stadium that already exists,’” Kristick said. “It’s far more complicated. It was a very proud moment for me — but also some disappointment for the cities that did not make it because of all the energy they put into it.”

Over the past two months, SportsTravel canvassed more than a dozen sources about the selection process for this insider account, including:

- The level of secrecy in which FIFA held cities in suspense

- Meetings FIFA held with cities after the announcement and in subsequent site visits

- The view from those who were left on the outside after the announcement

- A timetable for when a schedule is announced

- Who’s in contention to host the title match

[Inside the 2022 World Cup: What It’s Like Behind the Scenes in Qatar]

Announcement Day Anxieties

After a series of site visits and endless Zoom meetings, communication between FIFA and candidate cities increased in the final three weeks, including a series of follow-up contracts that each city had to sign. The Monday before the announcement, each city was asked to provide a congratulatory video from a local celebrity, with cities needing to turn the videos around within a 48-hour period.

“There were many requests that came in which we knew would only be seen or used if we won,” said Meg Kane, manager of bid coordination and external affairs for Philadelphia Soccer 2026. “It was clear that FIFA wanted to make the announcement special but also maintain the confidentiality of its decision up until the moment host cities were revealed.”

Leaders in each city also got reminders the night before the announcement about hotel and flight reservations for a weekend ahead with FIFA officials. “We didn’t realize these had come in until mid-afternoon when someone caught it in their spam filter,” Kane said. “At that point though — given how thorough FIFA had been in its planning and in protecting the decision — we just assumed every candidate host city had received it and didn’t read into it all that much.”

FIFA’s confidential nature led to whispers about individual negotiations; Burke remembers hearing “some cities still didn’t have an agreement in place and were working on it up until the last hour. I would have lost sleep for sure if that were the case in our city.” Journalist Grant Wahl reported on Substack that FIFA officials met with Los Angeles and Miami bid officials the morning of the announcement.

One thing was for sure: Nobody knew which cities would be announced until the broadcast.

“(With) the NCAA, a lot of times we’ll get a phone call beforehand so that we can brace ourselves or know what to expect and put a plan of action together,” Dallas Sports Commission Chief Executive Officer Monica Paul said. “That wasn’t the case with FIFA.”

“It was brilliant by FIFA because having all of us fulfill these criteria just contributed to the ‘we don’t know’ feeling,” Seattle Sports Commission President and Chief Executive Officer Beth Knox added.

What Knox also did not know was if her internet connection would hold up. FIFA’s announcement fell in the middle of a vacation in Tuscany she had planned to take before the pandemic, which she had rescheduled for this summer.

“I kept thinking, surely the decision isn’t going to be bumped into July, and of course we know the end of that story,” she said, laughing. “I almost cancelled the trip a couple times.”

Instead, Knox streamed the announcement “praying the bandwidth would work.” Thankfully for her, FIFA — after nearly a half-hour of empty talk — started the city announcements with the West region. After Vancouver, one of the two Canadian cities to earn bids, was announced, the next city named was Seattle. The Bay Area, Los Angeles’ SoFi Stadium and Guadalajara, Mexico, followed.

“It was a huge relief that Seattle was announced early on,” Knox said, because “I didn’t get to bed until 2:30 in the morning since my phone was blowing up.”

“It was brilliant by FIFA because having all of us fulfill these criteria just contributed to the ‘we don’t know’ feeling,” — Seattle Sports Commission President and Chief Executive Officer Beth Knox.

Next was the Central region: Kansas City was first, the smallest of the 11 U.S. cities given bids. Dallas and Atlanta followed.

“The last time we had a live announcement for an event we were pursuing was May 2016 when the Super Bowl was announced on NFL Network,” Atlanta Sports Council Executive Director Dan Corso said. “When (FIFA) announced Atlanta, it took us by surprise by announcing us in the Central Region — we thought it would be in the East. But when they said Atlanta, we were so happy we didn’t care what part of the country they put us in.”

Then came the rest of the Central region with Houston plus Monterrey and Mexico City from Mexico.

“We almost vomited when they went from Kansas City to Atlanta,” Houston 2026 World Cup Bid Committee President Chris Canetti said. “But they quickly pivoted back to Houston with the next announcement and it was a lot of joy after that.”

The East region was last with the second Canadian city, Toronto, announced in addition to Boston, Philadelphia, Miami and New York/New Jersey.

“Our local collaboration team wanted to engage the whole community and organized an announcement watch party in just a few days,” said Philadelphia CVB President and Chief Executive Officer Gregg Caren. “Philadelphia is a huge sports town with a thriving soccer community, so win or lose, we were going to celebrate everything that went into the bid. But we knew Philadelphia submitted a very strong bid to FIFA and were confident we would secure World Cup matches. It was incredible to hear Philadelphia’s name called.”

Replacing Fields with Grass

For those selected, next up was an initial workshop with FIFA in New York.

“It was very worthwhile getting together,” Corso said. “To see folks in person was exciting and it was like a fresh start especially after being named a host city. I think coming out of that it gave us a good idea of the next steps and timeline.”

Bid officials spent Sunday networking before a series of meetings on Monday. As one large group, FIFA outlined a series of timelines and expectations. Each group of city officials then went into a series of five, 45-minute individual meetings with various groups of FIFA officials — one with the tournament operations team plus meetings on commercial rights, stadium infrastructure, branding and messaging, and human rights and sustainability. At the end of the day, the entire group went for a closing dinner.

“I think the meeting struck the right tone at that time,” Canetti said. “It wasn’t very specific because nobody was ready to be specific on details, but it felt exciting. It was positive to speak to these people that you’ve never met before and you’ve only seen on Zoom just to start to build a working relationship.”

FIFA representatives have already visited each city since July. The big focus was venues and what modifications will be needed to meet FIFA stadium requirements; every city interviewed said any changes would be minor with one exception — several venues do not have grass surfaces, a FIFA mandate.

“We planned all along to put in a grass field,” Knox said of Seattle’s Lumen Field, which will also need to have corners at the field level expanded like every NFL venue. “It will probably go in around April 2026 so it has an opportunity to be fully ready.”

For some venues, the grass-laying process is already in intensive planning. NRG Field hosts the Houston Livestock Show in February and March 2026, the largest livestock exhibition and rodeo in the world, forcing organizers to be inventive in its scheduling.

“We’re not going to be able to take over the stadium until around April 1 and we have to build a grass pitch as though we were building a permanent field that was going to be there forever,” Canetti said. “It basically gives us about a 60-day window to do everything we need to do to build that pitch and be FIFA World Cup quality in June for matches. And all that needs to be done, by the way, in a retractable-dome stadium where sunlight is a challenge and we have to do other work. So it was a huge issue during the bid process.

“At one point, we were very concerned about our ability to meet the FIFA standard,” Canetti admitted. “But luckily we had a subcommittee focused on the pitch and on the grounds in the field. And they came up with a wonderful plan to be able to do the work that needs to be done in a manner that was satisfactory to FIFA once the rodeo has ended and in time for the first World Cup game.”

Some venues will require further work — Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas said Arrowhead Stadium needs $50 million for improvements, which local officials said may end up being lower as the process progresses. SoFi Stadium’s narrow field level will require extensive work, the amount and cost of which has yet to be determined. AT&T Stadium will need to raise the field level approximately 15 feet; Dallas officials showed FIFA two ways to prepare the field during its pre-announcement site visit, what the sight lines would be and how it would affect seating and ticket revenue.

“Obviously, we’d prefer to go the route that is least impactful from a financial standpoint,” Paul said. “But at the same time, we understand FIFA guidelines and dimensions and widths and other things that they need from a technical standpoint. At the end of the day, it’s their call in terms of what they would like this pitch to look like and the height that is needed.”

On the Outside Looking In

“Any of the final cities in the U.S. could have been rationalized as being a great host,” said Kristick, noting “covered stadiums certainly seemed to be attractive to FIFA. Whether that’s partially covered like a Hard Rock in Miami or fully covered, whether it be Atlanta, Houston or Dallas, that comes with a lot of assurances from FIFA from a weather standpoint that you don’t have to worry about the conditions.”

The first World Cup in the United States in 1994 — a 24-team event — had nine cities host matches. Five will host again in 2026, but no matches will be at the stadiums that hosted in 1994, including in Los Angeles, where SoFi Stadium was surprisingly selected over the Rose Bowl given SoFi Stadium’s logistical issues to be FIFA compliant.

“I’m not going to criticize FIFA’s interest in a stadium like SoFi; it’s a remarkable facility,” Kristick said. “Those of us who were around in 1994 look at the legacy and contribution the Rose Bowl has had for the sport — hosting a Men’s World Cup final, Women’s World Cup final, it’s one of the purest soccer stadiums we have in America. Emotionally, I was a bit disappointed that you don’t have part of the 1994 history included with the Rose Bowl.”

Of the four cities from 1994 that did not get bids for 2026, two sat out the process — Detroit and Chicago. Miami’s inclusion in 2026 is widely considered to be in the place of Orlando, which hosted in 1994.

“We were very optimistic, we felt like we had put a quality bid in place,” Greater Orlando Sports Commission Chief Executive Officer and President Jason Siegel said. “I think it’s the old expression you hear in sports: We can only control what we were able to do and what we were able to put in front of FIFA. We certainly had heard whispers about what was happening in many of the other cities, but we felt we were able to deliver a tremendous portfolio of opportunities for FIFA. We were disappointed and surprised.”

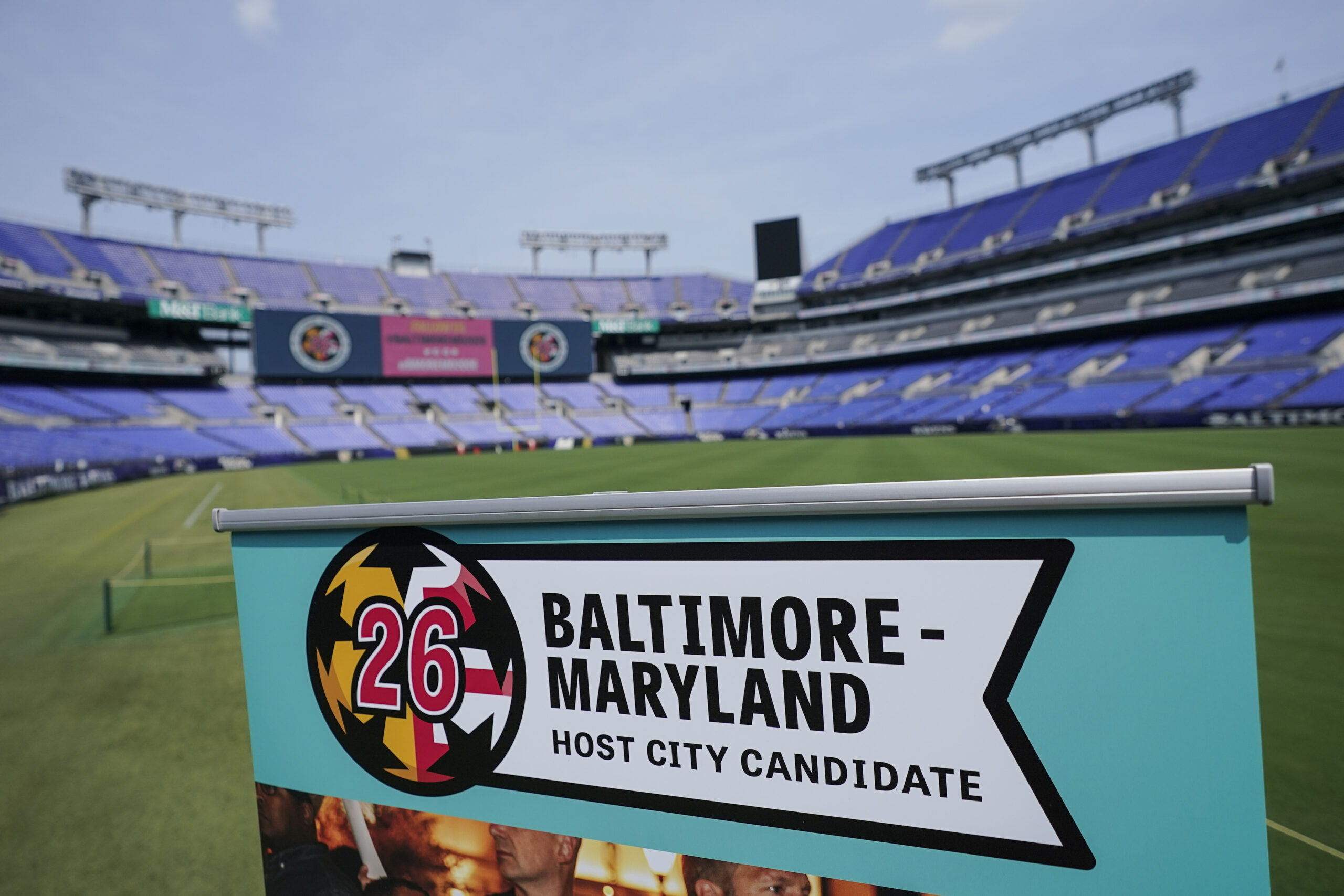

Then there was the big omission: “I was totally shocked about the (Washington) D.C./Baltimore bid not getting in,” one source said. Added another source, “How did that happen?”

The question still nags at Maryland Sports Commission Executive Director Terry Hasseltine, who led the Baltimore side of the bid.

“It was heart-wrenching,” he said. “It was FIFA that told us to (merge with D.C.). You were asked to do something and then you do what they tell you to do, sign all these new documents in good faith and in goodwill. To then not be awarded the event …”

Not getting the bid was one thing. It was another thing for Baltimore officials to see in the post-announcement press conference how FIFA President Gianni Infantino, with a smile, promised a Fan Fest in D.C., which hosted matches in 1994.

“You asked us to merge the bid,” Hasseltine said. “You asked us to carry the nation’s capital on the venue side and facilities side. There’s no reference to Baltimore afterward but ‘we’ll still do something in D.C.’ Not only did you step on us once by asking us to merge and carry the water on the bid, then you didn’t reference us in the closing statement. That was another little kick in the butt.”

FIFA’s Chief Competitions and Events Officer Colin Smith said for the cities that did not get bids, “there’s still lots of other areas of cooperation and working together and celebration.” Siegel said Orlando is “encouraged by the conversations and opportunities that still present themselves for the future.

“This bid was, in some ways, four or five times the size, scope and magnitude a traditional bid,” he said. “It gave our community the opportunity to allow our commission on homelessness to have a voice, our folks who are doing great work in the LGBTQ+ space a voice, workers’ rights, sustainability. I was really proud of the way the community came together.”

Hasseltine is open to a future with FIFA as well — to a point: “We’re not closing the possibility of something happening. But we have to be more mindful. Without the economic value of matches being played in our stadium, we can’t give away our training sites. We can’t be a base site based on the cost we were estimating because we don’t have the matches in our market.”

“It was heart-wrenching. It was FIFA that told us to (merge with D.C.). You were asked to do something and then you do what they tell you to do, sign all these new documents in good faith and in goodwill. To then not be awarded the event …” — Maryland Sports Commission Executive Director Terry Hasseltine

And Now, What’s Next

Each host city will have three representatives visit the 2022 World Cup in Qatar as observers before the announcement of how many matches each city will host; FIFA told them to expect an announcement in the summer of 2023. Under FIFA’s original plan, 60 of the 80 matches will be in the United States, while Canada and Mexico would each host 10 matches, all in the group stage.

Once the schedule is set, the logistical work will intensify. “We’re reaching all the way out to central and west Jersey for hotel accommodations and training facilities,” said Jim Kirkos, chief executive officer of Meadowlands Live CVB in East Rutherford, New Jersey. “And then you have the complexities that go with it such as security, transportation, food services. It’s a huge undertaking.”

Most cities hope to be in contention for a quarterfinal match or better; the quarterfinals, semifinals, third-place match and title match add up to eight matches for 11 U.S. candidates. How many matches each city gets will be crucial not only for revenue projections but also for fundraising to offset stadium modification costs.

“We’re all curious,” Canetti said. “We need to know exactly how many matches and we need to know at least an idea of what we’re looking at. I’m assuming that Houston will get group stage games and hopefully at least a quarterfinal game. But we’re out raising money and our partners are going to want to understand what the schedule looks like. So hopefully, the sooner, the better on that one.”

Stadium size will play a large part in where marquee matches are placed. While each U.S. venue has the minimum capacity for group-stage matches plus knockout round and semifinal matches, FIFA requires at least 80,000 capacity for the opening match and the final. The initial bid proposal listed Atlanta and Dallas as semifinal hosts with New York hosting the final. “The hosting concept we presented to FIFA had the World Cup beginning on the West Coast (with the opening match in L.A.) and shifting to the East Coast with the final being in New York,” Kristick said. “It’s a city that’s so representative of the world but also from a time zone standpoint, having a final on the East Coast could be attractive to the major European TV markets.”

For his part, “we really want the final and we’re hoping that we’ve done enough to attract it,” said Kirkos. “(New Jersey Governor Phil) Murphy has been great with Mayor (Eric) Adams and New York City. There’s been this close cooperation between the two entities and hopefully we’ve proven to FIFA that this region lives up to the values they want in a World Cup final.”

However, most observers now believe Dallas has the edge to host the final, although a recent ESPN report that it has already won the right to host the title match was brushed off as presumptuous. Dallas and Atlanta are also believed to be the leading candidates to host the International Broadcast Center, which would bring in thousands of hotel room nights to either destination.

“I would be disappointed if Dallas didn’t host a final or a semifinal,” Paul admitted. “I’d probably be more disappointed if we didn’t have a good conversation about it beforehand and ensure that we had a shot at it because I know what that stadium is and what it can do.

“I’ve been here 14 years in December, and I still go out and tell people who I am and what I do. And people will come up to me afterward and tell me in 1994 when Dallas hosted the World Cup what street corner they were on, what they were doing, what was happening in their lives, how there were signs in Spanish and English and the impact that had on people. The sky’s the limit in terms of what hosting a World Cup final could be for us.”

Until then, each city will continue to prepare and may be kept in the dark until FIFA announces a decision. Either way, the countdown has begun.

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000