A list of 12 game-changing stadiums in history compiled by the Smithsonian shows that the evolution of sports venues can trace centuries while staying true to a few core principles, said panelists during the SportTechie webinar “The Way Back: Designing Stadiums for the Future.”

The full list of stadiums picked by the Smithsonian dates to 566 BC with the Panathenaic Stadium in Athens, Greece. Of the stadiums selected, eight are post-1965 and five have been built in the 21st century including SoFi Stadium in Los Angeles, which is scheduled to open this fall, and Ras Abu Aboud in Qatar, which will be one of the stadiums used in the 2022 FIFA World Cup.

“We really tried to weigh breakthroughs in a number of key areas,” said Arthur Daemmrich, director of the Smithsonian’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. “One of those is the technology in building those structures, what it’s made of. … We wanted it to be about the issue of fan experience. The only reason we continue to build stadiums isn’t so millions of people can watch the game; they can do that at home. It’s so we can gather people in an intimate environment and that has changed over time.”

“Facilities that have long-lasting nature, they represent the place they’re from, the culture, the locale,” said Russ Simons, chief listening officer and managing partner of Venue Solutions Group. “They embody those cultural elements physically. There’s lots of new exciting designs but at the end of the day, it’s a combination of things starting with sense of place.”

The intrinsic nature of going to an event also matters. Daemmrich said one of his earliest sports memories is going to a baseball game as an 11-year-old at Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia “which most people don’t think of as a pinnacle of stadium design and yet, that green field sticks with me.”

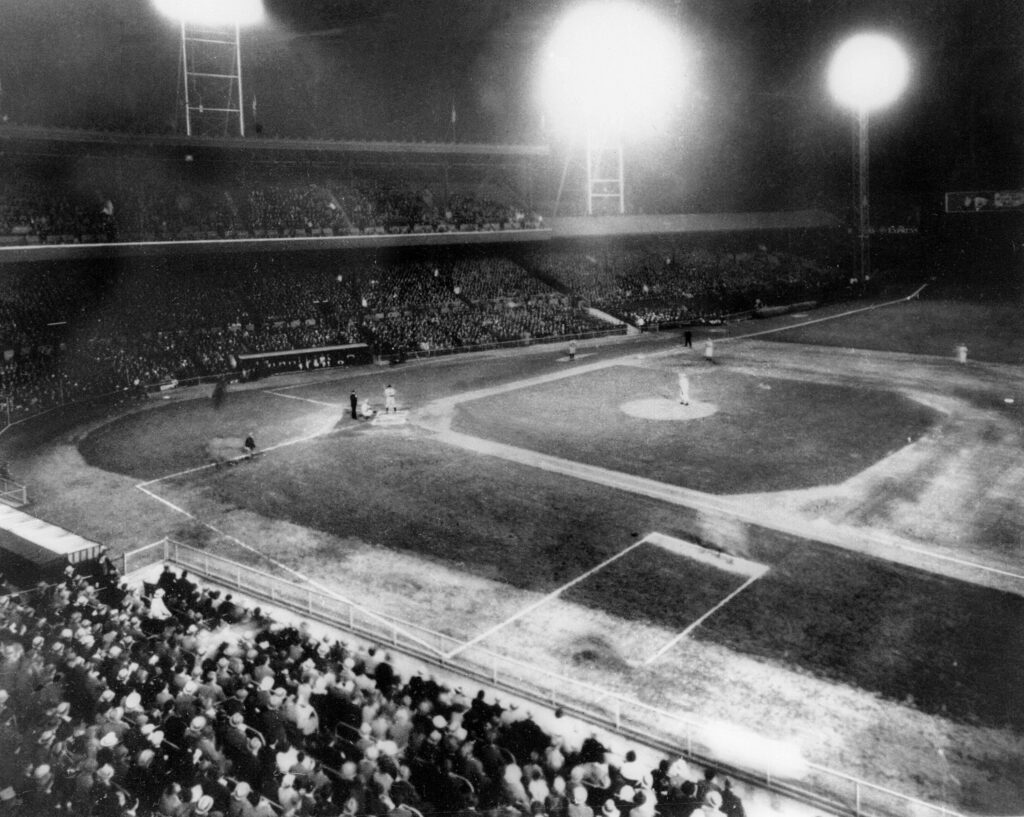

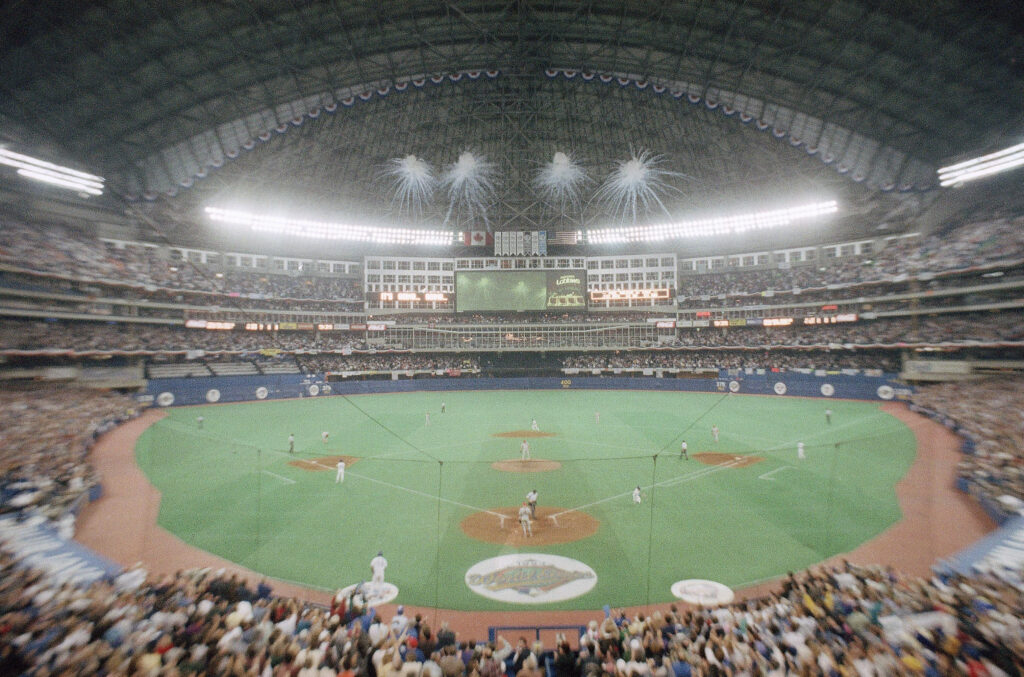

Four of the 12 venues highlighted are based in the United States. Along with SoFi Stadium, venues highlighted were Crosley Field in Cincinnati, which was the first Major League Baseball stadium to have lights for night games; the Astrodome in Houston, which brought in the era of multipurpose stadiums but also transcended design as a domed stadium; and the 1992 opening of Camden Yards in Baltimore, which is still seen as a design masterpiece.

“What happened in 1992 with the transformative moment of Camden Yards, it took away the cookie-cutter stadium and moved baseball back into the city and made it about nostalgia,” said Brian Mirakian, senior principal at Populous. “It was such a game-changing moment because of that.”

Revenue Drivers

Another gigantic shift has been in how venues are used to drive revenue for a team or league. What for decades was two tiers of seating can now be six or more with suites and club areas. Simons said when he was with Populous during the time of Petco Park’s development in San Diego, the architecture firm identified 27 spots in the ballpark that could be utilized for everything from weddings and meetings to corporate outings. The home of the Padres then drove regeneration throughout the downtown Gaslight district.

“One of the shifts in projects now is that they are part of a much broader development strategy,” said Mirakian, pointing not only to Petco Park but the London Olympic Stadium, a centerpiece of the 2012 Olympic Summer Games and now the home of the Premier League’s West Ham United. “It’s rare that we work on a project that isn’t part of some broader development now. It’s as much about the amenities that generate the revenue.”

Simons also had plenty of thoughts about the multipurpose stadiums that were built throughout the 1960s and 1970s (“multitasking is an opportunity to do several things poorly at the same time”) and the trend toward stadiums with sustainability in mind (“We talk about sustainability like it’s something that came from Mars. It’s our basic responsibility to treat our communities and resources with respect.”)

Need for Adjustment

Of course, how stadiums and venues will adjust in the future in a post-COVID world was also discussed. Daemmrich pointed out that there are photos from 1918 college football games with fans wearing facial coverings while the World Series that year was held in September — partially because of concerns over World War I, but also because of the Spanish flu pandemic.

“By human nature, we are resistant to change,” Simons said. “You are going to see ultimately that there will be physical changes incorporated into design.”

“Every great breakthrough in history comes from a moment of disruption,” Mirakian agreed. “We are certainly at a moment of disruption here. … This is a moment to create a better stadium that is safer from a health and wellness perspective. … There’s going to be a tremendous amount of innovation that comes out of this. This isn’t a moment of disruption we were asking for — but it’s the moment of disruption that we’re faced with. There’s going to be so many breakthroughs that come from this. We’re not going to return to designing the buildings we always have.”

12 Game-Changing Stadiums in History

566 BC: Panathenaic Stadium, Athens, Greece

80 CE: Colosseum, Rome

1908: White City Stadium, London

1912: Crosley Field, Cincinnati, Ohio

1965: Astrodome, Houston

1989: Skydome, Toronto

1992: Camden Yards, Baltimore, Maryland

2001: Sapporo Dome, Sapporo, Japan

2008: National Stadium, Beijing

2009: National Stadium, Kaohsiun, Taiwan

2020: SoFi Stadium, Los Angeles

2021: Ras Abu Aboud, Qatar

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000